The places Kurt Vonnegut called home didn’t just house him—they shaped the stories that made him legendary. From his Arts & Crafts childhood home to the Iowa City attic where he wrote Slaughterhouse-Five, these locations reveal how real-world experiences forged an iconic writer.

Let’s explore four key places that influenced Vonnegut’s life and work, uncovering their stories and what they offer curious visitors today.

Growing Up in Indianapolis: Vonnegut’s Early Years

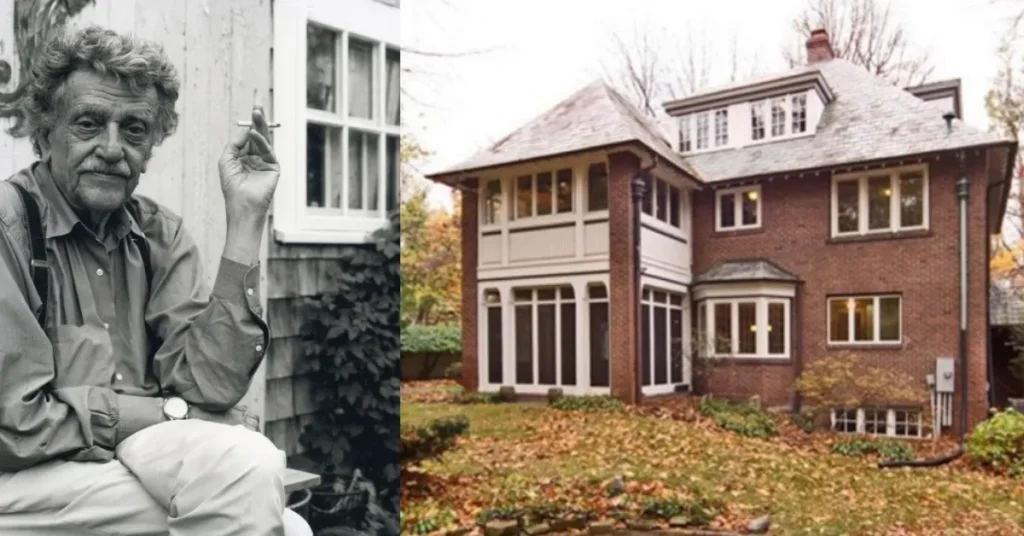

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was born in Indianapolis in 1922, and his family soon moved into a newly built Arts & Crafts style home at 4401 North Illinois Street. Built between 1922–1923, this Kurt Vonnegut’s House witnessed Vonnegut’s early years during a pivotal era in American history.

Their comfortable home reflected the Vonneguts’ status in Indianapolis—Kurt’s father was a sought-after architect who carried on the family’s design legacy in Indianapolis. Their residential dwelling featured classic Arts & Crafts elements: natural materials, handcrafted details, and an emphasis on simplicity.

Young Kurt’s childhood spanned the Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression, times that deeply influenced his worldview. His experiences here—family gatherings, early reading habits, and growing awareness of social inequalities during economic collapse—later surfaced in his writing.

Financial struggles during the Depression forced the family to move to a smaller home when Kurt was a teenager. This sudden upheaval became a recurring theme in his novels, where characters often face life-altering twists of fate that can reshape lives without warning.

Today, the childhood residence remains privately owned. While not open for public tours, literary travelers can view the exterior from the street. The property maintains much of its original character, with a small plaque identifying its significance.

Lake Maxinkuckee Summer Retreat

Before Kurt was born, the Vonnegut family established a summer compound on Lake Maxinkuckee in Culver, Indiana. This lakeside retreat, built by Kurt’s grandfather, Clemens, in the late 19th century, gave the family a seasonal escape from city life.

The compound included several cottages where generations of Vonneguts spent summers swapping stories and debating ideas. For young Kurt, these days on the lake contrasted sharply with urban Indianapolis. The freedom to explore, swim, and observe nature sparked his imagination and nurtured his storytelling abilities.

Vonnegut later described these summers as idyllic times that deepened his understanding of family bonds. The compound’s gatherings of multiple generations nurtured the compassionate outlook that defined his writing.

In his autobiographical work “Palm Sunday,” Vonnegut reflected on how these lakeside summers connected him to both his German-American heritage and midwestern values. You’ll spot echoes of these summers in his books—quiet lakeside moments contrasting with life’s chaos.

The lakeside cottages have changed hands many times over the years. Today, one historic structure known as the “Clemens Vonnegut Jr. House” operates as a vacation rental. Visitors can experience the same setting that influenced the author, though the buildings have undergone renovations.

Staying in the rental allows literary travelers to sleep where Vonnegut once spent his summers, creating a unique connection to the author’s personal history. The property management acknowledges the home’s significance, providing guests with information about the Vonnegut family’s time there.

The Vogt House: Iowa City’s Literary Landmark

This Queen Anne-style home on Newton Road hides a big literary history. Known as the Vogt-Unash House or the Kurt Vonnegut House, this Queen Anne-style home housed Vonnegut and his growing family during his time teaching at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 1965 to 1967.

Note: Research indicates there may be confusion about Vonnegut’s exact Iowa City address. Some sources suggest he lived at 800 North Van Buren Street, while others reference the Vogt House on Newton Road. Both locations are associated with his Iowa City period.

Built in 1880, the house features a distinctive corner tower, decorative woodwork, and a welcoming front porch—typical Queen Anne elements. While teaching at the Workshop, Vonnegut lived here with his first wife Jane and their children, occupying the upper floor while the owners resided below.

This period marked a turning point in Vonnegut’s career. At his desk in Iowa City, he began writing “Slaughterhouse-Five,” the masterpiece that elevated him from cult sci-fi favorite to a household name. The novel drew on his experiences as a prisoner of war during the Dresden bombing in World War II.

Here, Vonnegut spent months struggling to write about Dresden before crafting Slaughterhouse-Five’s groundbreaking mix of war memoir and sci-fi—a challenge he’d grappled with for 20 years. Something about the Iowa City environment finally unlocked his ability to address his war trauma through fiction, using his signature blend of science fiction, dark humor, and humanity.

In recognition of its importance, the Vogt House earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. The nomination specifically cited its connection to Vonnegut and “Slaughterhouse-Five,” acknowledging the home’s role in American literary history.

Today, the historic building remains privately owned but stands as a point of interest on literary tours of Iowa City. While interior access is restricted, visitors can view the exterior and imagine Vonnegut working on the manuscript that would change his life.

Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library

Though not a home, Indianapolis’ Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library feels like his true literary sanctuary and is the centerpiece of preservation efforts. Located on Indiana Avenue, the museum opened in 2011 and moved to its current expanded location at 543 Indiana Avenue in November 2019.

The KVML occupies a historic building downtown. It houses an impressive collection of artifacts, including his Purple Heart medal, Underwood typewriter, and personal letters. Most poignantly, it displays an unopened letter from Vonnegut’s father that arrived while Kurt was a prisoner of war in Germany.

Exhibits trace Vonnegut’s life from his Indianapolis childhood through his wartime experiences and literary career. You can pound keys on a replica typewriter, explore his anti-censorship battles, and see the actual Purple Heart he never bragged about. The space recreates elements of his writing environment, giving visitors insight into his creative process.

Beyond static displays, the KVML functions as an active cultural center with regular events, readings, and educational programs. The museum sponsors an annual “Night of Vonnegut” celebration, banned books events (reflecting the author’s strong stance against censorship), and writing workshops inspired by his techniques.

For dedicated fans, the research library contains rare editions, scholarly works, and archival materials available by appointment. This resource serves both casual fans and academic researchers exploring Vonnegut’s literary contributions.

Admission remains affordable ($8 for adults, with discounts for seniors, military, and students), making the experience accessible to a wide audience. The first Monday of each month is KVML’s Goodbye Blue Monday celebration with free admission to all. The museum operates from Wednesday through Monday.

The Vonnegut Architectural Legacy in Indianapolis

The Vonnegut family was already famous in Indianapolis, thanks to the family’s architectural firm. Vonnegut & Bohn, founded by Kurt’s grandfather and later joined by his father, designed many important buildings throughout the city.

The firm’s architectural footprint includes the Athenaeum (originally Das Deutsche Haus), the Indiana Bell Telephone Building, and numerous schools and civic structures. These buildings reflect the family’s German heritage and progressive values—qualities that would later emerge in Kurt’s literary voice.

The Athenaeum stands as a testament to the family’s cultural impact. This imposing Germanic building served as a social center for Indianapolis’s German-American community and embodied their commitment to physical fitness, arts, and education, values emphasized in the Vonnegut household.

Kurt often noted how his family’s architectural background shaped his thinking. In novels like “Player Piano,” he shows an architect’s attention to how physical spaces influence human behavior. His precisely constructed sentences reveal the same disciplined approach to creation that marked his family’s architectural practice.

Literary travelers can take self-guided walking tours of Vonnegut-designed buildings throughout Indianapolis. The city’s tourism office offers maps highlighting these architectural landmarks alongside sites connected to the author’s life, creating a comprehensive experience.

Visiting Kurt Vonnegut’s America

For those planning a Vonnegut-inspired journey, timing and preparation can enhance the experience. Indianapolis offers the richest concentration of sites, making it the natural starting point.

Spring and fall provide pleasant weather for exploring Indianapolis on foot. The museum hosts special events during these seasons, including Banned Books Week activities in September and birthday celebrations in November.

Iowa City’s literary scene thrives year-round, with the Iowa Writers’ Workshop continuing to produce influential authors. The university town offers walking tours highlighting its literary landmarks, including the Kurt Vonnegut House. Combining a visit with one of the city’s literary festivals adds context to Vonnegut’s time there.

Lake Maxinkuckee is best experienced in summer, when visitors can enjoy the same seasonal pleasures the Vonnegut family once did. Booking the Clemens Vonnegut Jr. House requires planning, as this unique literary accommodation fills quickly during peak season.

Before visiting these sites, reading key Vonnegut works enhances appreciation. “Slaughterhouse-Five” connects directly to the Iowa City period, while “Palm Sunday” contains reflections on his Indianapolis upbringing and family history.

Photography enthusiasts find rich opportunities at these locations, though respecting private property remains essential. The architectural details of the childhood home and the literary residence reward careful observation, while the lakeside setting offers scenic inspiration.

How These Historic Places Shaped His Writing

The physical spaces of Vonnegut’s life profoundly shaped the mental landscapes of his fiction. His childhood home‘s stability, followed by its loss during the Depression, taught lessons about fortune’s fickleness that appear throughout his work. Characters in novels like God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Breakfast of Champions often experience sudden shifts in circumstances that mirror this formative experience.

The Lake Maxinkuckee compound, with its multigenerational gatherings, informed Vonnegut’s creation of extended, unconventional families in his fiction. His concept of the “karass” in “Cat’s Cradle”—groups of people mysteriously connected across time and space—reflects these summer communities where diverse individuals formed temporary but meaningful bonds.

In Iowa City, the modest upper-floor apartment provided the quiet space Vonnegut needed to finally process his war experiences through fiction. The university town’s intellectual environment helped him transform traumatic memories into “Slaughterhouse-Five’s” innovative narrative structure.

Vonnegut himself acknowledged these connections between place and creativity. In a 1977 interview, he noted, “Where I write doesn’t matter much, but where I’ve lived matters tremendously.” He described his novels as “mosaics of place,” assembled from locations that had emotional resonance for him.

Scholars have noted how specific architectural elements from Vonnegut’s childhood appear in his work. The Arts & Crafts movement’s emphasis on craftsmanship and function over ornamentation mirrors his stripped-down prose style—straightforward sentences building complex moral arguments, much as simple wooden beams create strong structures.

Final Words

These 4 locations form a physical map of Vonnegut’s journey from privileged child to war veteran to literary icon. Each place contributed to the distinctive voice that made him one of America’s most beloved authors—a voice full of wit, heart, and truth bombs.

For readers and road-trippers, these sites create real links to Vonnegut’s world—proof that great stories grow from lived experiences. Through these spaces, we gain a deeper understanding of how physical environments shape literary imagination and how one writer turned his life map into stories we all recognize.