Roy Lichtenstein created some of the world’s most recognizable pop art, but his final series before his death in 1997 expanded his practice. This collection transforms his signature bold colors and black outlines into three-dimensional optical illusions that challenge how we see architecture. Walk around the sculptures to see them transform—corners appear to bulge outward from one angle and cave inward from another.

This project was the artist’s last major creative endeavor and shows how pop art could move beyond the canvas into our physical space. These sculptures continue to surprise museum visitors today with their visual tricks.

The 3 Houses That Changed Pop Art

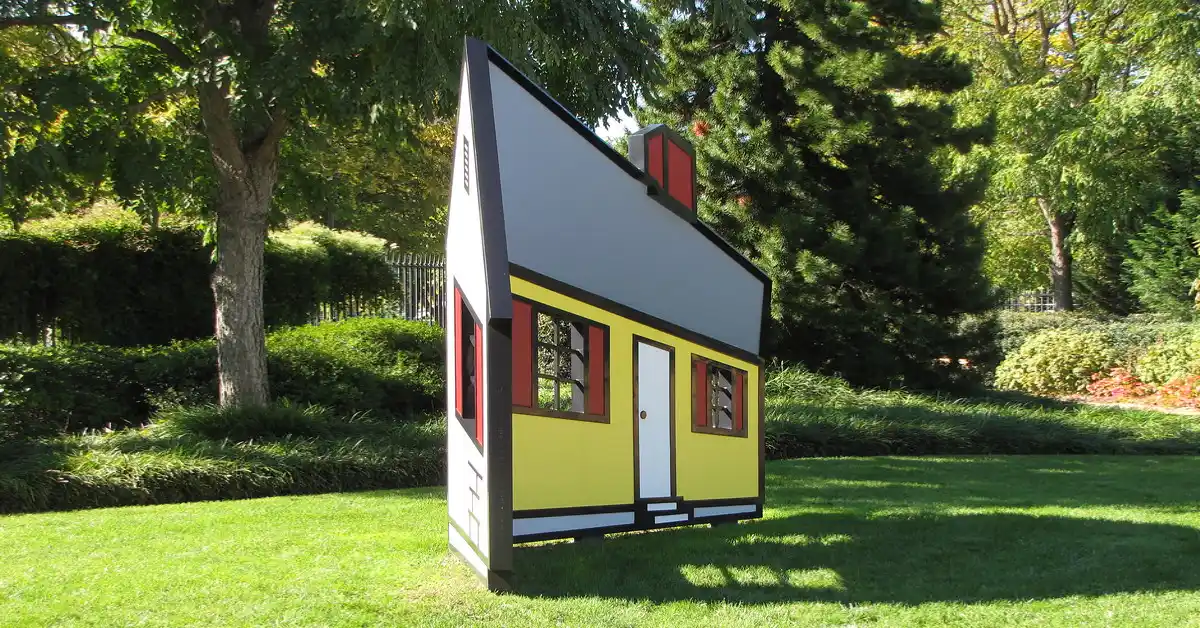

The series includes three sculptures—House I, II, and III—created in the late 1990s. Unlike Lichtenstein’s famous comic-inspired paintings, these works are large outdoor installations made from painted aluminum that create optical illusions.

Each sculpture resembles a simple cartoon-style house with bright primary colors, thick black outlines, and flat surfaces. The magic happens when you move around them—the same corner can appear to bulge outward one moment and push inward the next.

Lichtenstein designed all three pieces but only saw early versions before he died in 1997. The final sculptures were built later following his exact plans—House I was designed in 1996 and fabricated in 1998 by Lippincott, Inc., though installed at the National Gallery in 1999, while House III wasn’t completed until 2002.

These works marked a major shift for the artist as he explored how his distinctive style could work in three dimensions. They connect to his earlier paintings while exploring new territory, showing how he kept evolving right up to the end of his career.

How These Sculptures Trick Your Brain?

The sculptures manipulate depth perception through forced perspective. Walk up to one from a certain angle, and your brain insists the corner is pushing outward. Take a few steps to the side, and that same corner now seems to be caving in.

This happens because Lichtenstein used forced perspective—a technique that messes with how we judge depth. Your brain tries to make sense of what you’re seeing based on shadows and perspective lines, but these sculptures deliberately scramble those signals.

The illusion works through precisely angled walls combined with Lichtenstein’s signature style translated into 3D space. Those bold colors and thick black outlines make the effect even more dramatic by emphasizing shapes while flattening their appearance.

What makes these works special is that you have to physically move around them to get the full experience. Unlike paintings viewed from one spot, these sculptures invite you to circle them and watch as they seem to transform right in front of you.

House I

House I stands as the first and largest sculpture in the series. You’ll find it in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., where this piece measures about 9.5 × 14.5 × 4.3 feet.

With its red roof, yellow walls, and blue chimney, the sculpture looks like a cartoon house dropped into real life. The corner either sticks out or pushes in, depending on where you stand. From one angle, everything looks normal. From another, you’re looking at something that couldn’t possibly exist in real architecture.

Lichtenstein designed House I in 1996, though it wasn’t actually built until 1999, two years after he died. The National Gallery version is one of two—the other lives at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, South Korea.

Visitors circle the sculpture repeatedly, studying the illusion’s mechanics. Many take videos as they circle, capturing the moment their perception shifts.

House II

House II remains the most mysterious of the trio, with much less public visibility than its siblings. Unlike the freestanding sculptures that bookend the series, House II was designed as a wall sculpture, bridging the gap between Lichtenstein’s flat paintings and fully three-dimensional works.

This piece made brief public appearances at the Venice Biennale in 1997 and later at a 2008 exhibition in Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. House II (1997) measures 144 x 144 x 24 inches and is held in a private collection, rarely exhibited publicly since 2008.

House II continues the optical illusion theme but approaches it differently as a relief sculpture meant to be viewed from more limited angles. It represents an important step in Lichtenstein’s journey from his Interior paintings to the fully realized 3D sculptures.

The lack of information about House II highlights a gap in the documentation of Lichtenstein’s later works. Art fans and researchers are still hoping for more chances to study this transitional piece in the future.

House III

House III represents the fullest realization of Lichtenstein’s optical illusion concept. Sitting outside the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, this aluminum sculpture measures 157 × 210 × 60 inches and was built in 2002, five years after the artist died.

With its blue roof, yellow walls, and red chimney, this colorful structure creates a striking presence on the museum plaza. The illusion here is refined to perfection—from one angle, the corner juts outward; from another, it seems to collapse inward, creating a physically impossible structure that makes you question what you’re seeing.

The Atlanta weather hasn’t been kind to House III over the years. Recently, specialists had to carefully repaint the sculpture to match Lichtenstein’s exact color specifications after sun and rain took their toll. This restoration brought back the primary colors that make the piece pop.

Just like House I, there’s a second version of House III located at Dorothy Lichtenstein’s estate.

Breaking New Ground

The sculptures pioneered technical innovations in the 1990s, before digital fabrication became commonplace. Each one started as drawings and small models before being enlarged and built from aluminum panels.

Lippincott, Inc. used laser-guided tools to cut and weld aluminum panels at exact angles, ensuring the illusion held at full scale. The angles had to be exactly right, and the painted surfaces needed to maintain that signature flat, cartoon-like appearance despite existing in three dimensions. Lichtenstein collaborated with Lippincott, Inc., a renowned fabricator of large-scale sculptures, to engineer the precise angles and surfaces to construct these complex forms.

Lichtenstein chose painted aluminum for good reasons: it’s relatively light, holds up outdoors, and provides the smooth surface needed for his clean lines and flat colors. This choice does create ongoing challenges, though, as the paint must handle years of weather exposure.

These works helped pioneer techniques now common in public art but were cutting-edge for their time, bridging traditional sculpture with modern fabrication methods.

Where do These Houses Fit in Art History?

These sculptures mark an important turning point where pop art, usually associated with flat images, successfully expanded into immersive 3D space. They came at the end of Lichtenstein’s career, after he had already made his name with those famous comic-inspired paintings.

By the 1990s, Lichtenstein was pushing into new territory. The Houses evolved from his earlier work, creating hologram plates (the C-Project from 1994-1999) that he ultimately abandoned because he wasn’t satisfied with them. House III specifically grew from his Interior paintings, where he had started exploring perspective more deeply.

These works also connect to the broader public sculpture movement of the 1990s, when many artists were creating pieces designed specifically for outdoor spaces rather than museum pedestals. Lichtenstein’s contribution stands out for combining architectural forms with optical illusions and his instantly recognizable pop style.

Their interactive illusions resonate in today’s public art, encouraging viewer engagement that blend art experience with social sharing.

How the Houses Came to Life?

Lichtenstein didn’t just dream up these sculptures overnight. His process began with simple sketches where he played with different house shapes and optical illusion ideas. You can see him working out various angles and perspectives in these early drawings.

Next came the hands-on stage—building small cardboard or wooden models to test if the illusions would actually work in 3D. These mini versions helped him fine-tune the exact angles needed to create that wow moment when viewers walk around the finished piece.

He stuck with what worked best for him, color-wise: those trademark reds, yellows, and blues paired with bold black outlines on white surfaces. These simple, punchy colors make the optical tricks pop while staying true to his recognizable style.

For the final step, he partnered with specialized fabricators who could build his designs at full scale in aluminum. Every detail mattered—from the precise angle of each wall to the exact shade and finish of every painted surface.

Visitor’s Guide

The best way to appreciate these sculptures is to see them in person. The National Gallery’s Sculpture Garden hours vary seasonally (check website). House III is accessible 24/7 on the High Museum’s plaza.

For the full effect, approach House I from the west side and slowly walk counterclockwise. You’ll hit that moment when your perception suddenly shifts as you move past the corner.

House III sits outside the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. While you need a ticket to enter the museum itself, you can see the sculpture from the plaza. Morning light shows off the colors best, while late afternoon sun creates interesting shadows that enhance the illusion.

If you’re taking photos, the illusion can be tricky to capture in still images. Try shooting video as you walk around, or position friends at different angles to show how perspective changes everything. Time-lapse shots can also effectively demonstrate the shifting effect.

Why These Houses Still Matter?

These sculptures represent an important chapter in American art as one of the last major projects by a defining pop artist. They show how Lichtenstein never stopped innovating, expanding from flat comics to immersive optical illusions that you can walk around.

In the art market, these later works have gained increasing appreciation. While his comic-inspired paintings from the 1960s still bring the highest prices, In 2022, House I’s sister sculpture sold at Christie’s for $3.9 million, reflecting rising demand for Lichtenstein’s late works as collectors recognize their importance to his artistic journey.

Their influence extends to contemporary artists working with sculpture, architecture, and optical illusion. The playful approach to challenging perception continues in works by artists like Anish Kapoor, Olafur Eliasson, and Julian Opie.

Most importantly, these sculptures continue to delight visitors. Unlike conceptual art that might require background knowledge to appreciate, these pieces offer an immediately accessible visual experience that surprises everyone regardless of their art background.

They challenge viewers to question spatial perception, fulfilling art’s role in reshaping perspective around us. Decades later, they still stop people in their tracks, making them walk back and forth to experience again and again that moment when perception shifts.